How was Phosphate Deposited in Florida?

http://nrli.ifas.ufl.edu/hainescity.html

Florida’s rich phosphate deposits are marine

deposits that began to form millions of years ago when the sea covered the

state. During the Miocene and Pliocene

ages, or approximately 5-10 million years ago, biological and chemical changes

transformed phosphate that existed in the seas into the phosphate sediment that

we mine today. This phosphate stretches across the state and up the coast to

the Chesapeake Bay.

There are many theories about how Florida’s

phosphate deposit was formed. One of the most common is that during the Miocene

era, ancient seawater currents flowed onto topographically high areas. These

upwelling currents caused nutrient and phosphate rich waters to rise to the

surface of the sea that covered Florida at the time. This phosphate

precipitated from the seawater to form phosphate rich sediment that solidified

into nodules. Teeth, bones and waste excrement from marine life deposited along

with the nodules in layers within Florida’s limestone.

As time passed, sea levels dropped and the

phosphate and limestone layers were exposed as land. During the Pleistocene era, the marine

phosphate deposits were geologically reworked and re-deposited in a

concentrated form.

In Florida’s phosphate rich areas, fossilized bones

of the creatures that roamed the land and water when the state emerged from the

seas have been found in the pits created when phosphate is mined. The bones of

pre-historic creatures such as the mighty mastodons, saber-tooth tigers, bears,

whales, dugongs and manatees, camels, three-toed horses, six-horned antelope

and other ancient animals are clues to Florida’s history. The bones of the land

animals, which are mostly from the Pleistocene age (about 100,000 years to 1

million years old), are primarily found on top of the phosphate layer. The

remains of the marine creatures are mainly found within the Miocene-Pliocene

phosphate layer.

You will not find dinosaur fossils associated with

the Florida phosphate formation. The extinction of dinosaurs occurred about 65

million years ago, well before the lands began to emerge from the ancient seas

covering Florida about 25 million years ago.

Because of the many fossilized remains of these

land and sea creatures that have been found to be associated with the rich

phosphate deposit in central Florida, the region that has been the heart of

Florida’s phosphate industry has come to be known as Bone Valley.

How was Phosphate Discovered in Florida?

Some

three decades after phosphate rock was first mined in England to be used in

fertilizer, Dr. C. A. Simmons, who owned a rock quarry for building stone in

Hawthorne, near Gainesville in Alachua County, had some of his rock sent to

Washington, D.C. in 1880 for analysis. The rock was determined to contain

phosphate.

Dr.

Simmons launched the earliest attempt in Florida at mining and using phosphate

in 1883. His attempts were short-lived, but by1883 phosphate was also reported

at other locations in Alachua, Clay, Duval, Gadsden and Wakulla counties.

Although

Dr. Simmons is credited with the first discovery of phosphate in Florida, the

Florida phosphate boom of the late 1800’s was triggered after the 1889 discovery

of high-grade phosphate hard rock by Albertus Vogt near the new town of

Dunnellon in Marion County. Mr. Vogt had noticed fossil remains of prehistoric

animals in a nearby spring that reminded him of similar finds near phosphate

deposits from years earlier when his family had lived in South Carolina, where

phosphate was first found in the United States. Rock samples taken while

sinking a well on his property were determined to have very high phosphate

content. Vogt and a few other local citizens began buying up land in the area

and the first hard rock production began in 1889 by the Marion Phosphate

Company. This was followed by the Dunnellon Phosphate Company, in which Vogt

had ownership interest, in 1890.

News

of this great find spread. Thousands of prospectors and speculators flooded the

area and the great Florida phosphate boom had begun. By 1894 more than 215

phosphate mining companies were operating statewide.

The

boom brought wealth. Land that had been selling for $1.25 to $5 an acre sold as

high as $300 an acre. It was written

in1891 that “many a cracker homesteader who went to bed a poor man woke up in

the morning to find himself a capitalist.” The boom, however, was short lived.

By 1900, only 50 companies remained in operation.

Meanwhile,

while surveying for a canal in 1881, Captain J. Francis LeBaron, chief engineer

of a detachment of the U.S. Army Corp. of Engineers, discovered river pebble in

the Peace River, just south of Fort Meade, Polk County. Analysis of samples of

this pebble confirmed the presence of phosphate. This discovery, though, did

not draw much attention at the time.

In

1886 John C. Jones and Captain W. R. McKee, of Orlando, discovered high-grade

phosphate on land along the Peace River between Fort Meade and Charlotte Harbor

while on a hunting trip. This led to the formation of a syndicate known as the

Peace River Phosphate Company by Jones, McKee and a close group of associates.

They devised a scheme whereby they could acquire as much land as they wanted

while keeping land prices low. The group decided to tell local landowners that

the roots of the saw palmetto bushes, that covered the land for miles around,

were rich in tannic acid. Their story was to tell landowners that they intended

to need to buy their land to remove the bushes and extract this tannic acid

from the roots. They would then sell the land back to them for a song. Their

plan worked so well that they had soon acquired forty-three miles of riverfront

property.

Mining

activity along the Peace River proceeded both in the river itself and on the

adjacent land. So-called “River Pebble Mining” was the first to be exploited.

In 1888 Arcadia Phosphate Company launched the first tentative mining operation

in Bone Valley and made the first shipment of Peace River phosphate pebble

about a year ahead of the Peace River Phosphate Company.

The

first land pebble mining operations were undertaken by Florida Phosphate

Company at Phosphoria and the Pharr Phosphate Company at Pebbledale in 1891.

Because

of its high cost of production, river pebble mining could not compete with land

pebble and hard rock. As a result river pebble production, which peaked in

1893, ceased entirely by 1908.

Hard

rock mining, which dominated the early years of the industry, also had high

production costs relative to land pebble. In the early years, however, because

of it’s high quality, it was able to demand higher prices from the export

market. This market began to diminish in the early years of the century to such

an extent that, by 1906 land pebble production had overtaken hard rock. Hard

rock production continued to dwindle until mining finally ceased in 1965 in the

Ocala-Dunnellon region. The mining of

land pebble continues today in central and north Florida.

Phosphate

mining did not come to north Florida in any significant way until the 1960s

when Occidental Petroleum Company, like many petroleum companies at the time,

was looking for a way to get into the fertilizer business because it was

considered a profitable way to diversify.

There were no land or acquisition opportunities available to get started

in the central Florida mining district, but there were north Florida phosphate

reserves that were close enough to the surface to make the area equally

attractive as mining sites. Occidental went north and opened a mine in White

Springs where it mined phosphate until 1995 when the Potash Corporation of

Saskatchewan (PCS) purchased the operation.

Today,

after decades of consolidation and market changes in Florida’s industry, four

phosphate companies maintain mining operations: IMC Phosphates Company, Cargill

Fertilizer, Inc., PCS Phosphate – White Springs, and CF Industries, Inc.

The "Great Florida Phosphate

Boom" began in the 1890s, not long after high-grade phosphate was first

discovered in Marion County, as well as in the Peace River. Prospectors flooded

into Florida in the wake of the discovery and by 1894 there were over 200

mining companies operating in the state. But the boom was brief. Only 50

companies were still in operation by 1900. The industry has experienced

further, albeit slower, consolidation ever since. Only three phosphate-mining

companies operate in Florida today, including IMC, which hosted our field trip

to their mining site in central Florida. IMC is the largest phosphate mining

company not only in Florida, but in the world.

http://nrli.ifas.ufl.edu/hainescity.html

Pebble phosphate was discovered in the late

1880’s in central Florida near Ft. Meade, Polk County. Its discovery eventually

led to the demise of the hardrock deposit mining.

http://www.mii.org/stateinfo/FLHist.html

Mulberry Phosphate Museum

Florida's 130,000 acre rock phosphate ridge

and its giant pebble phosphate

fields are almost forgotten today http://www.floridahistory.com/inset44.html

Of all the phosphate in commercial

production: 90 percent is used for fertilizer for the production of food and

fiber; 5 percent is used for livestock feed supplements; 5 percent is used for

vitamins, soft drinks, toothpaste, film, light bulbs, bone china,

flame-resistant fabrics, and optical glass. Florida is the world leader in

phosphate rock production, annually producing 75 percent of the U.S. supply and

25 percent of the world supply. http://www.florida-agriculture.com/agfacts.htm

A Word About Our History…

In

the early 1880's, the area that is now Mulberry was sparsely settled territory

forested with longleaf yellow pine. Logging was the principal industry, and the

area was only a sawmill site. The district had no name and train crews put off

passengers and mail at a Mulberry tree beside the railroad tracks. Accounts

differ as to the date the discovery of phosphate in Florida triggered the

"boom years," but by the early 1890's the state was clearly in the grip

of "phosphate fever." So many shipments of prospectors' supplies were

marked "Put off at the mulberry tree" that a depot was built next to

the tree and named, of course, Mulberry.

http://www.mulberrychamber.org/ginfo.asp

Phosphate

Suniland Magazine

1925

Florida's greatest single present source of

mineral wealth is derived from her splendid deposits of phosphate, which she

has visible supplies of at least 250,000,000 tons. The phosphate of Florida is

known commercially as bone phosphate of lime, used throughout the world as the

basis of all fertilizers. Phosphate rock is found in many sections of the

world, the chief producing sections today being the French possessions of

Tunis, Algeria, and Morocco, Makatea Island, the Dutch West Indies, Japan,

Egypt, Australia and the United States, the last named country producing

approximately half of the world's supply. Present production in the United

States is confined practically to Florida and Tennessee, although what are

believed to be the greatest deposits of phosphate rock yet uncovered in the

world have been found in the Rocky Mountain regions of Idaho and Montana.

Two varieties of phosphate rock are found

in Florida, namely hard rock and land pebble, the latter accounting for 90 per

cent of the present production, this condition being attributable to the

inability of the Florida producer of hard rock phosphate to compete with the

Mediterranean product.

The developed hard rock deposits of Florida

occupy a hundred mile narrow strip of land paralleling the Gulf Coast,

stretching from Columbia County on the north to Hernando County on the south,

Passing through portions of the counties of Alachua, Marion, and Citrus.

Fifteen years ago hard rock production amounted to a half million tons a year,

valued at nearly $5,000,000, but now the output has fallen to less than 200,000

tons, due to the fact that this product is at present entirely exported. It

would stern, however, that the time will come when Florida hard phosphate rock

will be used extensively in conjunction with lime for the upbuilding of

Florida's less fertile soils.

Florida's pebble rock deposits are confined

to the counties of Hillsboro and Polk, in what is known as the Bone Valley

District. These mines at present are producing approximately 3,000,000 tons a

year, valued at about $10,000,000 representing about 90 per cent of the total

value of the phosphate industry of the state.

Phosphate mining in Florida is of the open

pit method exclusively, the overburden being removed and the rock mined by

hydraulic machinery, supplemented by mammoth dredges. The moving of the

overburden is a colossal task, it being estimated that the phosphate companies

of Florida remove more earth in a single year than were removed in the record

excavation year in the building of the Panama Canal.

There has recently been placed in operation

on Tampa Bay a $2,000,000 plant for the recovery of the finely divided

phosphates that have heretofore gone to waste. Under this process the phosphoric

acid is extracted and concentrated up to the strength necessary to combine it

with other phosphate rocks, a process which its inventors claim permits them to

produce a triple phosphate, the phosphate ammonia of which is available. There

are millions upon millions of tons of finely divided phosphates in the old

phosphate waste piles, and it is believed that a large portion of this supply

will be recovered.

Source:

Excerpt from: Agassiz, Garnault. "Florida in Tomorrow's Sun."

Suniland, Nov. 1925, Vol.3, No.2., Pgs. 37-45; 88-94; 113-133

http://fcit.usf.edu/florida/docs/p/phosphte.htm

Phosphate Mining in Florida

|

|

The area in Central Florida where

phosphate is found is known as Bone Valley because deposits often contain

fossils of prehistoric creatures including mastodons, saber-tooth tigers and

teeth from 40-foot sharks. Phosphate deposits in Florida are among the

richest and most accessible in the world. Although there are several theories

about how the deposits were formed, many experts believe the ocean covered

what is now Florida about 10 million years ago. |

|

|

Phosphate ore is found from 15 to 50 feet

below the ground, generally in equal parts of sand, clay and phosphate rock.

Draglines - or huge cranes that could easily hold several full-sized cars -

remove the top layer of soil, and scoop up the phosphate matrix. The matrix

is put in a pit where high-pressure water guns create a slurry that can be

pumped to a processing plant. |

|

|

The "beneficiation" process

separates the sand and clay from the phosphate rock. After the largest

particles are removed, the slurry is run through a hydrocyclone that uses

centrifugal force to remove the clay. Waste clay is pumped to a settling

pond. Sand and sand-sized phosphate particles - called "flotation

feed" - are put through a process which uses chemical reagents, water

and physical force to separate the sand and phosphate. Remaining sand is

pumped back to the mine where it will be used to restore the site when mining

is complete. The rock is trucked to chemical processing plants, like Piney

Point. |

|

|

Phosphate ore must be chemically

processed before it can be used as a water-soluble fertilizer. Mixing it with

sulfuric acid creates phosphoric acid that's used in fertilizer. When

sulfuric acid reacts with phosphate to form phosphoric acid, it produces a

slightly radioactive byproduct known as phosphogypsum. According to the most

recent figures from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, there

are a billion tons of phosphogypsum stacked across the state and 30 million

more tons are generated every year. Because it is radioactive, federal

regulations ban its use in almost every situation. However, several pilot

programs show that it may be a cost-effective alternative to fill material

used for building roads. |

|

|

Reclamation efforts developed over the

past 30 years have been so successful that thousands of acres have been

donated to local governments for parks. Providing habitat for wildlife also

is a top priority, and researchers have identified 348 species of animals

using reclaimed phosphate mines including the threatened scrub jay. |

|

|

Florida provides 75 percent of the

phosphorous used by U.S. farmers and about 25 percent of world production.

Critical for root and flower development in all plants, phosphorous is

quickly depleted in soils and must be replenished regularly if fields are to

remain fertile. |

http://www.baysoundings.com/sum02/behind.html

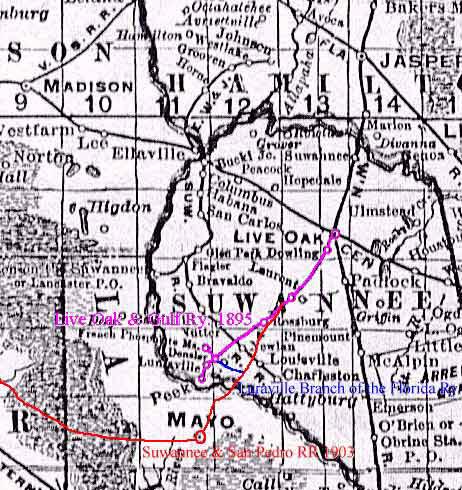

The French Phosphate Company

operated two train sets of mining equipment here. The two 0-4-4 narrow gauge

locomotives were built by Porter as c/ns 1446 and 1587. C/n 1446 was

built in January of 1893 and 1587 was built in March of 1895. Both locomotives

were built with 7x12 inch cylinders and were 23.75 inch gauge. The official

name of the company was the " Cie des Phosphates de Franco". Note

that there were two different styles of ore cars used. Don Hensley Collection.

Phosphate was in great demand in

Europe following it's discovery in Florida. At that time Europe had very little

resources at all in phosphate. Later on the mineral would be discovered in

French and British colonies through out the world. But in the late 1880's and

to the beginning of the First World War, Florida was the main source of

phosphate for the Europeans. Both France and Great Britain maintain

mining companies in Florida. The French Phosphate Company first mined one of

the rarest forms of North Florida phosphate called plate rock. This was located

near Citra, Florida near Ocala. The French even operated a 60 cm (23-7/8")

gauge railroad at Citra, purchasing a locomotive from Porters. Around 1894 this

mine finally was running out of ore and a replacement was needed to keep

production up. The French decided to enter the Luraville Phosphate area by

buying up many of the independent mines in the area.

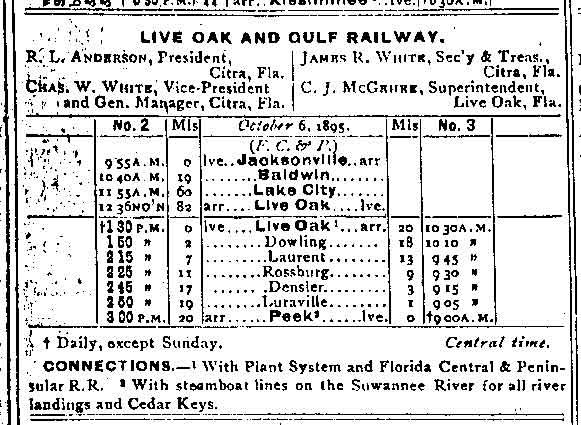

However a railroad was needed and as

the LOL&DBRR was stalled, the French contacted their American business

agents, Charles & James White of New York, NY, who was in Citra, managing

the French properties. Another business partner was Robert L. Anderson of

Ocala who also was invited in. Together these three men incorporated the Live

Oak & Gulf Railway Company on January 4, 1895 with $5,000 in capital stock.

Anderson was elected president, Charles White became vice-president, while James

White took over the duties of secretary and treasurer. At the same time they

took over the roadbed and assets of the Live Oak, Luraville & Deadman's Bay

Railroad, but not its charter. Originally Robert Anderson had 5 shares, Charles

White had 10, and James White had 35. But on March 5, 1895 the capital was

increased to $150,000 though only the $5,000 was issued at this time. Also W.C.

Remick and Thomas McIntosh of the LOL&DBRR was brought on board and issued

5 shares a piece by transferring 5 shares each from Charles and James White's

shares. Then a mortgage account was started with the New York Security and

Trust Co. of New York, NY.

Construction began in February at a

fast pace, one mile of track had been laid by March 1, 1895. James R. Morehead,

listed as Roadmaster, supervised the construction. By May 15, 1895, the entire

12 miles of track from the end of Dowling's Log Railroad to the Suwannee River

at Peek, 2 miles west of Luraville had been finished. $100,000 worth of bonds

were issued by the mortgage company. Even Dowling's Log Road had been

reconstructed, so there were 19 miles of new track laid. But the Live Oak &

Gulf still needed to purchase Dowling's 7 miles of grade. The mortgage did not

include the purchase of this property, so the LO&G went to the Florida

Central & Peninsular with empty pockets and open hands. After signing a

preferred connection agreement and hiring a FC&P man as a General Manager

to operate the company, the big road loaned $5,000 for the down payment of

Dowling's Log Road with the track as collateral.

Operations began on May 1st with

Charles McGehee of Live Oak as General Manager. McGehee was also the FC&P

station agent for Live Oak and would also be involved in many business ventures

through out North Florida, from owning a machine shop/locomotive rental

business to operating a large sawmill. The Live Oak & Gulf owned two

locomotives, more than likely Charles Dowling's old locomotives. The engine

house was on the mill property in Live Oak. The company also owned one

passenger car with a matching baggage car. Two flat cars rounded out the

roster. Operations were good for the first year of business, over 9,000 tons of

phosphate was hauled for a revenue of $11,388 and they earned $1,854 hauling

general freight and $1,036 carrying passengers. Expenses amounted to only

$6,080 which left plenty for paying the interest on their debt. The nearby

Suwannee River Railroad was by now abandoned, though it would live on in maps

and schemes for the next 10 years.

The French Phosphate Company was also

booming, it had moved their 60 cm gauge railroad from Citra, and

purchased a new locomotive from Porter and some new ore cars. A two mile branch

line was built from Densler Jct. (just east of Luraville) to the Phosphate

Mills. Now the Luraville phosphate operations were served by two complete

narrow gauge train sets hauling the hand dug rock from the pit to the washing

and drying mill. Now here is how they mined phosphate back in the good old

days. First a hollow pipe is hand driven into the ground for soil samples.

Samples are then analyzed for their content of phosphate and their content of

iron. Iron in this case is bad, if the sample is over 3 percent the phosphate

can not be used. Also the phosphate percentage had to be over 75 percent,

though phosphate in this area was usually a rich ore, averaging around 90

percent. But the iron was the bane of this operation in Suwanne County as

many times it would be over the 3 percent level, up to 7 or 8 percent, which

ruined the phosphate as a fertilizer. Once a large body of good phosphate was

discovered, a pit would be dug by shovel and pick, usually by local African

Americans from Live Oak. The removal of this overburden as it was called was

help out by the narrow gauge tram roads, which could haul it out. Once the pit

was dug down to the phosphate deposit, which was in the form of large boulders

laying over the native limestone, the boulders would be hand picked and loaded

onto the ore cars and hauled to the mill. The mill would then crush the rock to

pebble size and then the pebbles would be laid onto a bed of wood, in an open

shed, the wood bed is lit and the ore was dried to remove the moisture for

shipping. Once dried it would be loaded onto box cars and hauled to

Jacksonville for loading onto steamships for France.

The 1890's method of digging a pit. Here is the

first step of clearing the land, using shovels and mules pulling scrappers. Don

Hensley Collection.

As we can see the Live Oak & Gulf

was built to haul phosphate which it did very well during its first year of

operation in 1895. Assuming an average of 20 tons per car, over 450 carloads of

ore were hauled out to Live Oak. A mixed train and a phosphate extra was run

daily during this period. 1896 was even better, hauling out 10,800 tons of ore

in 540 cars. One of the locomotives was scrapped or sold that year, but they leased

a locomotive from William E. Boone of Jacksonville, Fl to help take up the

slack. The only known photo of a LO&G train has this W.E. Boone locomotive

up front. W.E. Boone was an ex-master mechanic of the Florida Central &

Peninsular (SAL) and had his shops at their yards in Jacksonville. He would buy

old motive power from his old employers as well as many of the other roads

nearby, like the Southern, Central of Georgia and the Savanah Florida &

Western (ACL). He was partial to Rogers, but he also bought other cast offs as

well. The photo of the LO&G locomotive appears to be an old Danforth Cooke

engine. W.E. Boone locomotives are easy to identify, they always had his

initials ( W.E.B.) under the cab and they were numbered from 90 to 135. He

leased and sold these old engines through out Northern Florida and Southern

Georgia to logging and mining concerns as well as to shortlines.

http://www.taplines.net/feb/loandg2.htm

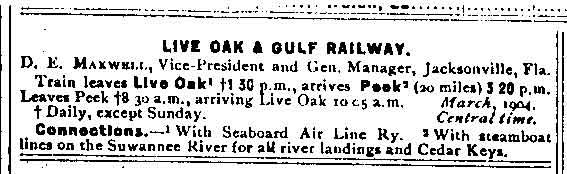

Now 1897 was a bad year and a turning point

for the Live Oak & Gulf, phosphate production was stopped at the end of

1896 after it was noticed that the iron content was too high. No ore at all was

shipped in 1897 and the railroad had to change from a mining road to a general

carrier. They had been developing freight in the area by carrying finished

lumber from the Bache Brothers saw mill at Peak on the Suwannee River as well

as carrying bricks from the brick works at Luraville. Sand was also carried,

this being the only product of the mines during this time, but it was not

a big item. Log trains belonging to Thomas Dowling also help bring in needed

income. The railroad also connected with the Suwannee River steamers at Peak,

which gave them access to Branford and Cedar Key. 1898 was just as bad, both of

these years they were just able to meet their general expenses, but they fell

behind in interest payments. By 1899 they owed Thomas Dowling $4,682.06 which

he sued for and won an injunction over the LO&G, which forced a sheriffs

sale on the 7.55 miles of track. The White brothers promptly paid for this

track out of their own money and the road was still intact. The Whites were

planing to expand west across the Suwannee into Lafayette County to some mining

properties they owned but these plans were spoiled by the introduction of a new

railroad in the area, the Suwannee & San Pedro RR.

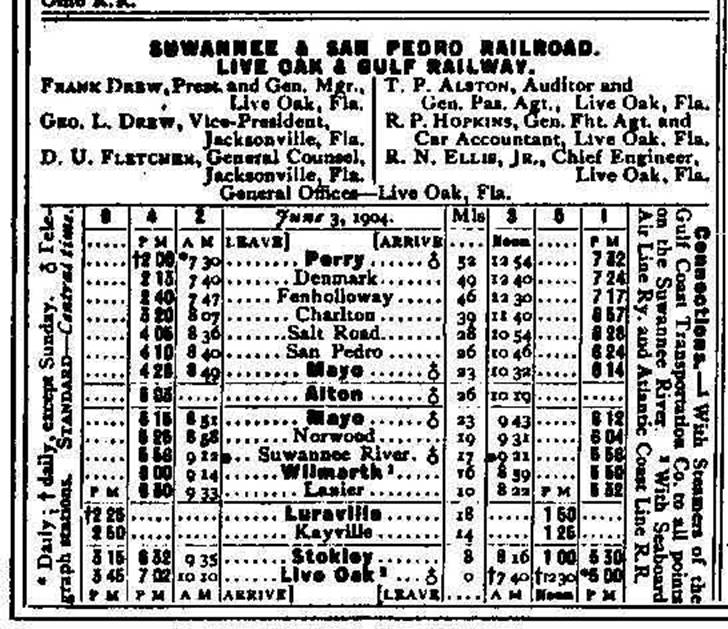

The Suwannee & San Pedro was

incorporated on July 1, 1899 to build from across the Suwannee River,

connecting with the Live Oak & Gulf by barge. This railroad was started by

the Drew Lumber Co. to reach timber areas they had bought from the State

Internal Improvement Fund. The Drews were at first was going to use this road

to log the area, dumping the logs into the river and rafting them to their

sawmill at Branford. However when the principal owner died, former Governor

George Drew, his two surviving sons, Frank and George, took over the project

and changed the scope of operations. Now they plan to build a large on-site

sawmill near Mayo, which would be called Alton, after their father's birthplace

in New Hampshire. A railroad from Mayo to Live Oak was now planned, though they

still built the western portion across the river from the LO&G. This was

done on purpose, as the LO&G expansion plans were known, and the S&SP

did not want any competition on this side of the river. However the LO&G

did enjoy record profits during 1899-1900, as it cost the S&SP over $10,000

to ship their two locomotives and 800 tons of track over the LO&G.

The first part of 1899 saw a small

resurgence in mining on the LO&G, around 100 carloads were shipped that

year. But 1900 saw no phosphate mining at all, luckily they had all that

S&SP construction traffic, as they made over $12,000 in profit that year.

Also that year negotiations were begun with the S&SP over two points,

purchasing the railroad in its entirety or leasing a portion of the road. As no

agreement could be made about purchasing the S&SP decided to lease 9 miles

of the LO&G for its entry into Live Oak for $1200 a year. This agreement

was reached on November 11, 1900 and the S&SP busied itself with

constructing the missing portion. The affairs of the S&SP and its

construction will be not be told here as its a story to be told on its own.

The Live Oak & Gulf in 1901 was

still making good money carrying the construction materials of the S&SP and

they carried quite a few passengers as well, over 6,000 persons rode the train

that year. Thomas Dowling was still operating log trains over the

road as well. The phosphate mine was still closed but they didn't need it

during this period. 1902 was the first year of operations on the S&SP so

freight on the LO&G dropped thirty percent that year. And then the LO&G

got caught up in the feud that developed between Williams and Middendorf

of the Seaboard Air Line and Frank Drew of the Suwannee & San Pedro. While

details of the feud will not be given here for lack of space, it pretty much

boils down to this: Drew being a lumberman with a railroad, would not sign the

preferred connection agreement with the SAL, due to the fact the lumber

rates to Jacksonville was too high. Williams and Middendorf who financed the

construction of the S&SP were outraged and the poor LO&G was caught in

the middle. Using the LO&G as a pawn, the SAL bought the line from the

Whites. But because the lease on the 9 miles had already been signed, SAL was

bluffing and the Drews knew it, it. The Drews out bluffed SAL by threatening to

build their own line into Live Oak. With their bluff called SAL dropped out and

the Southern Investment Co. took over the road in 1903 and they entered into

negotiations with the S&SP about the eventual purchase of the LO&G.

This happened on June 1, 1904, when they paid $47,800 for the Live Oak &

Gulf. Part of the LO&G was abandoned at this time, from mile post 9 to just

east of Luraville and the trackage between Luraville and Peak was also

abandoned. However the S&SP built a connecting line from their mainline at

Wilmarth north to the LO&G trackage at Luraville. The Luraville trackage,

station and mine spur was kept intact and operated by the S&SP over this

new branch line.

The Live Oak & Gulf tale ends on

June 30, 1905, when the LO&G and the S&SP were merged into the Florida

Railway. The Florida Ry. operated the Luraville branch and the original 9 miles

of the old LO&G for the next eleven years, but the feud with the SAL

finally caught up with the Drews and the railroad closed down at the end of

1916, not seeing a train until 1919 when the Drews finally pulled all the rails

up. Phosphate traffic never rebounded to the levels of the first two years. The

French company was purchased by the Mutual Phosphate Co. which operated the

mines for a while. The First World War completed the destruction of this

industry at Luraville as Europe was too busy with the business of war, and

peacetime agricultural pursuits were laid aside. However Frank Drew in 1915-16

tried to replace his Luraville Branch with a two foot gauge railroad using the

old equipment of the French Phosphate Co./Mutual Phosphate Co. but it was

already too late to save his crumbling empire. He was inspired by his son's

description of narrow gauge military railroads in Europe, which he planned to

duplicate in Florida. At one point in the 1920's he tried promoting this idea

with many of the railroads in Florida, but only the Florida East Coast was

interested in the possibility of using narrow gauge in the Everglades but never

took him up on it.

http://www.taplines.net/feb/loandg3.htm

All text and images

in Tap lines are copyrighted 2004 and any Commercial use is reserved and must

be cleared by written

permission by Donald R.

Hensley, Jr. and/or the individual authors and/or photographers.

Click here for terms of use.

History of

Phosphate

Source of Phosphorus

The phosphate rock deposits in central Florida were formed five to fifteen

million years ago, a time when the state was covered by the ocean. Because

phosphorus-rich sea water allowed marine organisms to thrive, large amounts of

organic matter periodically accumulated on the ocean bottom. As the organic

material decayed, phosphorus was released into the sediments, forming phosphate

nodules and phosphatizing some marine animal remains. As the sea level

fluctuated, the phosphate was concentrated by erosion, forming the deposits

that are mined today.

Discovery of Phosphate

Rock While surveying the Florida wilderness in 1881, Captain J. Francis LeBaron

discovered phosphate pebbles in the Peace River south of Ft. Meade. Soon after

this major discovery, the speculators came. Traces of phosphate were found from

near Gainesville south to Charlotte Harbor.

Mining

Early methods of

mining river pebble were time-consuming, due to natural obstacles. In river

pebble mining, the workers had to walk into the river and pry the rock loose

with crowbars, picks and oyster tongs. Rock was loaded by hand onto barges and

then transported to washers.

Early methods of

mining river pebble were time-consuming, due to natural obstacles. In river

pebble mining, the workers had to walk into the river and pry the rock loose

with crowbars, picks and oyster tongs. Rock was loaded by hand onto barges and

then transported to washers.

The first pumps used to mine the pebble

were installed in dredge boats in the early 1890s. The 8-inch pump, which ran

on steam engines and boilers, produced an average daily yield of 35 to 45 tons

of pebble. However, high production costs and increasing competition from hard

rock and land pebble mines forced the decline of river pebble production in the

mid-1890s.

The center of activity for hard rock mining

was Dunnellon, Florida. Early methods of excavation included the use of picks

and shovels, wheelbarrows, mules and wagons. The workers endured long hours;

accidents caused by mining conditions and machinery were not uncommon.

Once pried loose, rock was thrown upon a

mesh screen which allowed clay and finer materials to pass through. Next, at

the washer, rock was placed on a screen of parallel bars measuring 2 to 2-1/2

inches apart. Streams of water washed the finer materials through the screen.

After the rock left the washer, it was hand-sorted to be dried. Hard rock

mining was short-lived, though, and by 1891 production began to decline.

Land pebble mining surged ahead with

cheaper and more productive mining methods. Removal of the overburden was

accomplished with large hydraulic and steam shovels. After rock was washed into

a sump hole, the resulting slurry was removed by centrifugal pumps and carried

to the washer.

After years of experimentation, hydraulic

methods were introduced around 1902. In addition, electricity began to replace

steam power. The mining operations were greatly improved by eliminating dredges

from the pit area and pumping the matrix to washers on land.

The industry suffered a mild setback with

the agricultural slump at the turn of the century. Business recovered, however,

and in 1913, Florida assumed its position as industry leader, producing 82

percent of the total U.S. production. Worldwide competition began to increase,

though, and by 1930, Florida land pebble phosphate held only 28 percent of

total world production. Today, Florida produces about one-quarter of the

world's phosphate rock.

The phosphate

industry made great expansion strides after World War I. New business methods

were developed along with technological advances. A breakthrough occurred in

1920 when Bill Carey introduced the dragline. Carey, president of the W. F.

Carey Company, had been awarded an overburden stripping contract from the

Southern Phosphate Company. This dragline had a 136-foot boom and was powered

by a diesel engine. Others quickly saw the advantages it provided - savings on

manpower and an increase in production. By the 1930s, draglines could remove

between 600 to 700 cubic yards an hour.

The phosphate

industry made great expansion strides after World War I. New business methods

were developed along with technological advances. A breakthrough occurred in

1920 when Bill Carey introduced the dragline. Carey, president of the W. F.

Carey Company, had been awarded an overburden stripping contract from the

Southern Phosphate Company. This dragline had a 136-foot boom and was powered

by a diesel engine. Others quickly saw the advantages it provided - savings on

manpower and an increase in production. By the 1930s, draglines could remove

between 600 to 700 cubic yards an hour.

Another equally important discovery was

that valuable phosphate particles could be removed from former waste products.

Messrs. Broadbridge and Edser of the Phosphate Recovery Corporation patented a

processing method in 1928 known as the "oil flotation process." This

would enable companies to recover up to 95 percent of the phosphate material

previously discarded.

What started as a fledgling industry more

than a century ago is now Florida’s third largest industry, behind tourism and

agriculture. The phosphate companies - led by giant IMC Global Inc. - directly

or indirectly account for more than 50,000 jobs, and they produce 75 percent of

the nation's phosphate and about one-quarter of the world's supply.

Plants

In the early 1840s, scientists discovered that treating phosphate rock with

sulfuric acid made the phosphate rock more soluble, changing the phosphorus to

a form more easily used by plants. That discovery paved the way for development

of the phosphate industry.

IMC Global Inc. takes pride in being among

the phosphate industry's most cost-efficient producers. Six manufacturing

facilities (three in Florida and three in Louisiana) can produce about eight

million tons of concentrated phosphate products a year for virtually every kind

of crop grown in the world.

The strength of IMC Global Inc. is the

result of a combination of factors: the economies inherent to large-volume

production; innovative application of technology; skilled in-house maintenance

advantages; and a commitment to operating procedures that enhance product

recovery while emphasizing worker safety and environmental protection.

Uses for Phosphate Rock

About 95 percent of the phosphate rock mined in Florida is used in agriculture.

Of this, 90 percent goes into fertilizer and 5 percent into livestock feed

supplements. The balance is used in a variety of products, including common

household items such as soft drinks, toothpaste, bone china, film, light bulbs,

vitamins, flame-resistant fabrics, optical glass and shaving cream.

http://www.imcglobal.com/general/education_corner/phosphates/history.htm

HISTORY*

* Taken from Historic Hawthorne Florida

Survey and Plan, Florida Division of Historic Resources and the City of

Hawthorne, University of Florida, 1996. Permission granted by Dr. William

Weismantel, UF

.

A Narrative History

Setting

Hawthorne is in rural southeastern Alachua County, very close to the boundary

with Putnam County. Observers have continually commented on two features about

Hawthorne: it has been a crossroads, and it is located in an area of natural

beauty where sportsmen have found abundant fish and wildlife. Today Hawthorne

continues to be a place where two rail lines join, and where two heavily

traveled highways cross. The traveler on SR 20 can drive about 30 miles east

through Putnam County to the St. Johns River, or 15 miles to Gainesville, largest

city in and county seat of Alachua County. The north-south road, U.S. 301,

takes drivers about 30 miles south to Ocala, rapidly growing seat of Marion

County, or 70 miles north to Jacksonville. In any of the four directions, the

travelers pass open space filled with forests and lakes. Other small

communities are located along the routes. Most of them, like Hawthorne, date

from the mid-nineteenth century. Along the routes in fall and spring, masses of

wild flowers bloom, birds fly overhead, and signs tell of outdoor recreation

such as at Lake Lochloosa south of Hawthorne. In winter the great oaks and

pines are bright in the sunlight and the chilly mornings do not discourage

fisherman who are trying their luck on one of the numerous lakes in the Hawthorne

vicinity. In summer people find that the waters of the four hundred or so lakes

provide hours of pleasure. The environment has long attracted settlers to the

Hawthorne area.

Early residents of the Hawthorne vicinity

The Timucuan Indians were the residents of what is now southeastern Alachua

county when the Spanish encountered them early in the 16th century.

During the two and a half centuries when Spain controlled Florida, the

Timucuans, exposed to disease and hard work, died out. The Creek Indians from

Georgia began to move south, seeking land in Florida. In 1750 the Creek chief

Sac-a-faca claimed the land which is now Alachua County; he was known as

Cowkeeper. The name Seminole was given to these Creeks; one derivation is from

the word Cimarron, which means runaway. Gradually, the name was applied to all

the Florida Indians. Like the Indians, American settlers crossed into Florida

territory to get land. Spain encouraged the newcomers, hoping to build stronger

settlements in Florida. Conflicts between the American settlers and the

Seminoles over land, and over the Indians providing refuge to runaway slaves,

were frequent. Responding to American complaints, in 1818 the United States

government sent troops under General Andrew Jackson into Florida. This action

led to the First Seminole War, which lasted three years until Spain, unable to

protect her interests, ceded Florida to the United States. Territorial Governor

Andrew Jackson had two major tasks: to clear up Spanish land titles and to make

Florida safe for American settlers. Eventually, the land grants were recognized

by the United States. Problems with the Seminoles recurred, slowing settlement,

but not stopping it. In 1824 Alachua County was created by the Territorial

Government, with the town of Newnansville, northeast of present Gainesville, as

County seat. Clashes with the Seminoles continued, erupting into the second

Seminole War in 1835. There were no roads in Alachua County to bring in

supplies for soldiers, and the fighting was sometimes intense. By July 1836

destruction of settlements had occurred south of the road that led from Black

Creek to Newnansville, south of the Bellamy road, and from Picolata on the east

to the present site of Hawthorne. Settlers were concentrated at the larger forts

and towns, and often had to be supplied from government rations. Many man were

not farming, but were away from their families, fighting the war. A stop to the

conflict came in 1842.

Beginning of Hawthorne

With a period of relative peace, settlers could return to their homes and grow

crops. The 1840s were the period when settlement of the Hawthorne area began.

According to Jess Davis, the origin was the establishment of the Pleasant Grove

Baptist Church after 1840. Daniel Morrison constructed a mill to grind corn;

the mill became the nucleus of a small settlement about one mile east of

present-day Hawthorne. The United States government passed the Armed Occupation

Act in 1842 which enabled a man to claim a 160-acre tract of land as long as he

cleared at least five acres, built a house, and lived there for five years. The

law made available 200,000 acres starting at Newnansville in Alachua County

south to the Peace River, except for coastal property and land two miles from a

fort. It was expected that the Act would provide a barrier to Indian raids.

Although the Act must have induced settlers to enter Alachua County, the

numbers must have been small as the population from 1840 to 1850 increased

formally 2282 to 2524. The land office in Newnansville opened in 1843, just

before Florida became a state in 1845.

Florida Statehood

Florida was admitted as a state even though the population was small and lived

in frontier conditions. Nearly all the settlements were in North Florida. The

third and final phase of the Seminole Wars prevented attention to other

pressing problems. Still, the land office in Newnansville was opened for

homesteaders outside the Spanish grant areas. Land surveys and government plats

were authorized (Winsberg, 1988, and 1995 Florida Almanac). In 1850 the

United States Congress passed an Act to enable states to reclaim the

"swamp lands" within their limits. The lands were given to the states

by the Federal Government . The new state of Florida received land which it put

aside in the Internal Improvement Fund. One person who acquired land from the

Florida fund in 1861 was C. F. Stokes. This land was later sold to Calvin

Waits, and is now part of present-day Hawthorne. Veterans of the Seminole Wars

could also claim land grants. One veteran who did so was James Madison

Hawthorn, who had come to Florida from Madison, Georgia, with his wife,

Parasade McIntosh. The exact date of his arrival in Florida is not clear.

According to Lee Baker, there is evidence that his great-grandfather, James

Hawthorn, born 1811 in Georgia, bought land 15 miles east of present day

Gainesville, Florida in 1834 (Gainesville Sun,

Mar. 25, 1979). The family Bible lists names and dates, proving that the

surname Hawthorn did not have an 'e' at the end. A study of the Hawthorn

family, however, indicates that James and Parasade came around 1850 (Jolley

& Jolley, 1878). Whichever is the correct date, Myrtle Hammond Cole,

lifelong resident of Hawthorne, wrote that James traveled on a barge across

Lake Santa Fe from Waldo, and when he saw the beautiful orange groves near

Morrison's Mill, he decided to settle in the vicinity and bought land. Orange

groves and water attracted more settlers; some lived near James Hawthorn; the

area had the name Jamestown. The name Graball was also used, supposedly started

by Negro slaves, who said the merchants grabbed all their money (reported by

Hattie Knabb). In 1853 settlement in Alachua County was influenced by railroad

construction. An election and picnic were held at Boulware Springs where the

voters determined that the county seat would go from Newnansville to a new town

on or near the soon-to-be-completed railroad-Gainesville. All mail addressed to

Morrison's Mill was sent to Gainesville to be picked up by any citizen of the

community who happened to be visiting there. It was brought into the mill where

it was distributed. This led Morrison Mill settlers to seek a post office to

avoid delays. In 1854 a post office was established at Morrison's Mill,

according to the Chronicles of Florida Post Offices. Benjamin W. Powell was the

first postmaster, followed by John Peacock, William H. Register, Calvin Waits,

Thurlow Bishop, George H. Bates, Lawrence J. Stokes, and James F. Sikes, whose

service ended in March, 1879. In 1859 the First Baptist Church of Hawthorne was

completed (no longer exists.) The first train on the Florida Railroad that was

started in 1855 in Fernandina arrived in Gainesville on April 21. The future

looked bright for Alachua County, as the area was at peace. The final phase of

the Seminole Wars that began in 1855 ended in 1858. Veterans of the wars were

eligible to receive grants, James Hawthorn was awarded land that was west of

what is now the Hawthorne town lake, and north of what were the holdings of

Calvin Waits. The 1860 census document of Alachua County's 17th

Division, which includes Hawthorn town, listed blacksmith Capell, country store

owner Calvin Waits and another store owner, John Peacock, carpenter John

Cannon, master carpenters Willis Cannon and W.R. Craig, and physician W.W.

Johnson. The other occupations were farmers and farm laborers. The growth of

the small settlement was once again interrupted by war.

Civil War

The railroad tracks from Gainesville to Cedar Key were completed in 1861, just

in time for the Civil War. Florida's chief contributions to the Southern Army

were white males, beef cattle, and salt. There was some fighting in Alachua

County, around Gainesville. The newly laid railroad tracks were damaged. Even

during the war years there was some development in Hawthorne. The First Baptist

Church congregation secured land from Calvin Waits for a new building in 1862.

The oldest house in Hawthorne is said to have been built during the war on

Johnson Street of the Jamestown settlement by Mr. Tillis. A sizable house,

known as the Tillis-Gay house, it dates to 1863, according to a member of the

Gay family, Mrs. Ella Gay, who resided there until her death in 1983. Ella's

husband, Earl Gay, was the son of the Gays who lived in the house after Mr.

Tillis. Earl, who was well known in the community, and served on the Alachua

County School Board for 17 ˝ years, added a concrete block to the house, which

is made of coquina block, building material that was used again in Hawthorne.

The gymnasium of the Hawthorne High School is named after Earl. Ella operated a

millinery store in her house and later worked in Spivey's General Store, a

small structure on Johnson Street that was typical of such establishments and

was popular with townspeople. Ella sold the first Camel cigarettes to appear in

Hawthorne. She served her community and her church; the Fellowship Hall in the

Methodist Church was named after her.

After the Civil War

The end of the Civil War marked a decided change in the history of settlement

in Florida. At the beginning of the war 6% of Florida population lived south of

Gainesville; by 1900 28% of Florida population lived south of Gainesville.

Alachua County did not experience the rapid growth of southern Florida, but

development did occur after the war. With a good climate and soil, Alachua

County attracted capable farmers, including newly freed African-Americans from

South Carolina and Georgia who came seeking land. The diversity of crops was

surprising; around the Jamestown area, farmers shared in the County's harvests

of cotton, oranges, sorghum, and other crops. Other jobs developed near

Gainesville as railroads were constructed. The Florida Railroad which came into

Gainesville was rebuild and acquired a new name, the Atlantic, Gulf and West

India Transit Company. Education was a concern in Jamestown. Mrs. Forward of

Palatka was the first teacher to come into the area; she came in the Civil War

period. In 1869 a log cabin served as the school; the schoolmaster then was Dr.

Clark. The sawmill came, along with other activities bringing more people, and

the little town outgrew its school. In early 1871 a new two-story frame

schoolhouse opened on Johnson Street. The lower floor had schoolrooms; the

upper floor was used for the Masonic Lodge, which dates from 1872 (information

from histories by Buchholz and Davis).

An Important Two Years - 1879-1881

In 1879 James Hawthorn completed the first plat of the "Town of

Hawthorn"; the plat shows 34 blocks with a church at the northwest corner

of May and Johnson Streets. This plat was not recorded until March 16, 1908.

The first confirmed discovery of phosphate rock in Florida was made in 1879

near Hawthorne by Dr. C.A. Simmons, who began mining it there in 1883, but he

ran out of capital (see Florida Phosphate Industry by A.F. Blakey and

Sara Drybe; Alachua County 1880-1900 - A Sesquicentennial Tribute, ed.

J.B. Opdyke, published by the Alachua County Historical Commission in 1974).

Zonira Hunter Tolles, writing a history of Melrose, stated that it was the

discovery of phosphate that brought attention to the Jamestown settlement, and

caused the move of the post office from Morrison's Mill to Jamestown. In 1870

the post office was opened in Jamestown. The first postmaster was Lawrence J.

Stokes. That same year the two settlements of Jamestown and Waits Crossing

merged and were known as Jamestown. The next year at a public meeting the town

was renamed Hawthorn upon the request of James Hawthorn. (An E was added to the

city name, probably unintentionally, by the railroads; the post office resisted

the change until it became official in 1950. To prevent confusion, the spelling

"Hawthorne" is used in this history.) Subsequent postmasters were

James Bell, Lorenzo Bell, John L. Brown, William H. Berkstresser, T.J. Hammond,

William H. Berkstresser, Nina Berkstresser, Mrs. Kirby Smith, Leslie A.

Sherouse, Clara E. Sherouse, and William Baker, who served in the 1950s. Nina

Berkstresser and her sister, Helen Middleton, told some family history to

Frances Stephens around 1970. Berkstresser family members first came to Florida

from Pennsylvania in the early 1880s. The son, W.H. Berkstresser, after the

freeze destroyed the family groves, had more than one occupation. He bought a

two-story house on Johnson Street; it served as post office on the ground

floor, and the family lived on the second floor. Mrs. Berkstresser made ice

cream to sell, and they had soft drinks and small goods for sale. Mr.

Berkstresser also built the house next door for his elderly mother. It was then

occupied by Mrs. Godon Middleton, and has stayed in that family. People claimed

their mail from Postmaster Berkstresser at the entrance on the first floor of

the building. The house today has been remodeled; the present owner, Ina Kay

Morgan, is a granddaughter of W.H. Berkstresser. People were moving into the

area because of the excellent hunting and fishing. In 1880 W.S. Moore moved

from Tennessee to Hawthorne to be a writer; he soon became an outdoors man. The

era of railroad construction was in full force in the 1870s and it was 1879

that brought the railroads to Hawthorne. Not every town had the advantage of

two rail lines, with trains heading toward each of the four points of the

compass. The Florida Railroad, which had built from Fernandina to Gainesville

by 1859 and to Cedar Key by 1861, organized a subsidiary, the Peninsular

Railroad, to complete its pre-war plan for a branch from Waldo to Ocala and

beyond. The 1861 grade had continued in a straight line through Orange Heights,

Campville, and Hawthorne, and today underlies several miles of Holden Park

Road. But when track-laying crews reached Hawthorne in 1879, they installed a

curve and headed for the fish, vegetables, and fruit of Lochloosa, Island

Grove, and Citra. At the same time, crews of the smaller Florida Southern

reached the area, building from Palatka to Gainesville; it was the intersection

of the two lines that came to be called Waits Crossing. The north-south line

became part of a large, reorganized Florida Central & Peninsular in 1888,

and the FC&P became one of the largest components of Seaboard Air Line RR

in 1900. The east-west line was taken into Henry Plant's system in 1895, and

the Plant lines were absorbed into the Atlantic Coast line in 1902. Initial

construction was not easy because not everyone wanted the railroads. Mrs.

Laughinhouse-Stephens told how some settlers met the railroad track layers with

shotguns. Her father, who was the railroad track foreman in charge of getting

the tracks through the towns, said that the law was if the tracks were laid and

the trains passed over them, then the tracks were secure and could not be taken

out again. The crews often finished laying track during the night; the train

ran early in the morning, and the land owners woke to find the deed done. One

landowner who held significant acreage welcomed the railroad. James Hawthorn is

said to have donated land to entice the Florida and Southern line to located

west of the town lake. Hawthorne was incorporated in 1881; this was validated in

1883 and again in 1887 (see Laws of Florida, Chapter 2382, Acts of 1883 , and

Chapter 4654, Acts of 1887). The Waits Crossing plat was recorded in August,

1881; there were 11 blocks south of Jamestown. Waits Crossing derives its name

from the crossroads formed by the Florida Southern Railroad and the Peninsular

Railroad. There were additional plats by Waits in 1882 and 1883.

History, part II

Hawthorne life in the 1880s

W.S. Moore opened the first hotel in 1882. He put

together different structures, one build by the Moores, one purchased from the

railroad, and one that had been the two-story schoolhouse building. The school

building had been located across the main street from the Moores. W.S. Moore

moved it with logs and mules. The sections of the hotel were linked together by

a porch. The hotel had the first running water in town, supplied by a tank and

windmill. Sportsmen from the north filled the hotel in season, enjoying the

hunter's breakfasts and giant dinners.

The Gainesville Sun article on the celebration of Founder's Day in

Hawthorne (March 30,21,1979) by Barbara Crawford gives some examples of life in

the community. In 1883 a lively bit of frontier life occurred; James Pascall,

the town marshal, was shot by John Fullenlove, who had been incarcerated in the

lockup and fined for being drunk. Citizens complained about the condition of

the public roads, especially the Praire Creek bridge on the Hawthorne Road

which went to Gainesville. The north-south road, Johnson Street, went through

Hawthorne, crossing the road to Gainesville in the northern part of town.

Carl Webber, who published Eden of the South in 1883, described Hawthorne

as located at junction of the Florida Southern and Peninsular Railways.

Hawthorne had a fine Baptist Church, some five or six stores, two hotels, two

cotton-gins, two wagons, a blacksmith, a livery and feed stable, and sawmills.

A good academic school was open, and there was a newspaper, Jess Davis wrote

that the newspaper was the Hawthorne Graphic. He mentioned prominent

citizens T.J. McRae, the Adkins brothers, and R . B. Smith, being landowners,

railroad agents, and merchants. T.J. McRae was known around the entire area; he

is mentioned in a book about Melrose, Florida , as a prominent Hawthorne

businessman. R.B. Smith farmed a 200 acre farm, one hundred acres of which he

planted to corn and Sea Island cotton. He also had an eight-acre orange grove.

Hawthorne flourished as an agricultural center. In June 1883 the Weekly Bee,

a Gainesville paper, reported that Hawthorne should not brag about its apples,

as Gainesville had the finest in the state.

Zonira Hunter Tolles in her Melrose history gives a picture of the interactions

among the communities in the region due to the improved technology of the

period, when the towns had trains, steamer service, and telegraph service. When

the steamer Alert from Waldo connected with the F. C. & P. railway, the railroad

from Green Cove Sprints, and the hacks from Hawthorne on the Florida Southern

railway brought in a lively crowd of all ages to socialize and dance in

Melrose. In 1884 there was a major train wreck of the Florida Southern near

Gainesville; news was telegraphed to Hawthorne of injuries to J. F. Hammond and

John McRae.

In other news the local papers described the 1885 hit of roller skating, saying

that skater L. Wertheim went out the window of a two-story house 18 feet from

the ground, landed on his feet, and went on skating.

In 1885 merchant T. J. McRae, who operated a general store and stable in

Hawthorne, was appointed to the Alachua County School Board. Along with his

brother, he owned a 500-acre farm, which was sizable for the area. (Source ...

history of Alachua County Schools.)

The Official Path Finder, a reprint of the Florida State Gazetteer

and business directory of 1886-1887, listed Hawthorne as one of the railroad

junctions of Florida, being a station for the Florida Railway and Navigation Company

with Waits Crossing being a station for the Florida Southern Railway; these two

had separate depots one half mile apart. An ad by the Hawthorne Spring House at

the Waits Crossing by C. J. Schomerus, proprietor, said that the great kidney

and liver cure spring was close to the house. The Florida Railway and

Navigation Company line took travelers from Fernandina on the Atlantic south

through many stops; in Alachua County, Waldo, Orange Heights, Dixie, Hawthorne,

and Lochloosa. Silver Spring in Ocala, Marion county, was a favorite

destination. At Hawthorne the traveler could get the hack line for

Melrose.

In 1887 the Alachua Advocate ran a list of people living in the

immediate neighborhood of Hawthorne: M. Hall, M. Hinson, J. Holder, J. Fennell,

J. Tompkins, J. M. Hawthorn, J. Denn, G. Ford, Mrs. McNabb, Mrs. Dering, Mrs.

Graddick, Mrs. Tompkins, M rs. Tyner, Mrs. Fennell, Mrs. Styles, Henry Smith

(colored), Jack Jenkins (colored), and H. Montgomery (colored).

A subdivision called Hawthorn was recorded with six large lots in May, 1887. It

was near the crossroads of the two major rail lines.

In 1889 a committee was appointed by the Baptists to look after the cemetery on

their land. Members of founding families of Hawthorne are buried there, with

gravestones visible today.

Hawthorne's active life in the early 1890s

The 1890 Census showed Alachua County as having 20,449 acres in cotton, with

Sea Island cotton bringing up to $100 per bale. The County also produced

tobacco, cane sugar, and molasses. Many of the workers were African-American

who came to Alachua County to get land (Sowell, FHQ 1985). Generally,

the African-Americans worked in agriculture, domestic service, laboring jobs,

and on the railroad.

The Center Hotel/McMeekin house was build on Johnson Street in 1890. A new

Baptist Church building was constructed in 1891 with Joseph McCarroll as the

contractor. Gus Martin, who was born near Hawthorne in 1894, wrote that the old

building was moved south on Johnson Street to about where the old two-story

school that became part of the Moore Hotel stood. The Methodist Church

cornerstone is dated 1891. The building lot was purchased for $55 from James

Hawthorn. The town hall was the scene of many entertainments, ice cream

suppers, school plays, traveling shows. It was also the Justice of the Peace

courts. Frank Price was the Justice of the Peace and Mayor of Hawthorne.

In 1891 there was a cry from Susan Theresa Carlton, a new baby girl, the sixth

girl born to a family living four miles south of Hawthorne. The Carltons later

bought a home in Hawthorne so that the children could attend school easily.

Susan became a nun; as Sister M. Regina Carlton, SSJ, she described Hawthorne

in a book she wrote about growing up in Florida. She wrote about the small town

set amidst the orange groves and lakes. It enjoyed prosperity, with its main

road being Johnson Street, which had stores and large tourist accommodations

such as the Moore Hotel. The city was a meeting place for people like salesmen

traveling east and west from Gainesville to Palatka, and north and south

between Starke and Ocala. A famous boardwalk almost joined the two train

stations of the two railroads serving the town, the Seaboard with its station

in the northern section of Hawthorne and the Atlantic Coast Line which crossed

the Seaboard at right angles toward the southern end of the town having its

station there. The boardwalk served the businesses, and formed a promenade for

young Hawthorne girls who used the train arrivals to show off their best clothes.

Importance of schools in Hawthorne

Hawthorne early gained a reputation for educational opportunities. The

townspeople refuted the criticism of rural schools as inadequate, and fought to

keep their schools (History of Alachua County Schools). The birth of Chester Shell in 1892

was important, because he would grow up to secure educational facilities for

colored children. Gus Martin described how his father, Robert H. Martin, built

a house close to town so that his six children could walk to school. Gus said

his first day in school was in 1890; Professor W. F. Melton was principal and

Mrs. Melton taught the primary grades in the small frame building that later

became the home of the Stringfellow family. Mr. Harry Stringfellow was

postmaster in a little building owned by Mrs. McGinnis located just south of

Johnson's drugstore. The small city was thriving; citizens felt strongly about

the importance of their school and resisted the move to consolidation of

schools proposed by Alachua County. The townspeople feared that Hawthorne

students would be sent to other communities to school.

The great freezes

The beginning of winter in 1894-95 was mild; the orange trees were sprouting

when a terrific freezing spell hit the area and remained for several hours.

Temperatures as low as 11 degrees were recorded in North Florida. Every orange

tree in the Hawthorne area froze; Sister Regina remembered children sticking

their fingers into the fruits and sucking juice while the owners calculated

their losses. Hawthorne residents decided to form a special taxing district to

raise revenues to fund the school after the freeze. Another freeze in 1899

signaled the end of the orange industry. The packing houses became dust

gatherers, and farmers were despondent until Henry Flagger came to the rescue

by lending money for seeds and expenses.

Flagger carried produce on his railroad, and the farmers learned to grow

vegetables for the growing cities of Florida. The era of truck farming began.

Willie Carlton became postmaster in Micanopy and the family moved there. The

Carltons continued to return in summers to their farm near Hawthorne where they

grew produce that they sold in Hawthorne on weekends (Sister M. Regina, "Time

Exposure", Florida Living, April 1994).

Prosperity returns

After the turn of the century, development continued in Hawthorne. Jess Davis

wrote that R. A. Smith and T. C. Holden started a turpentine still; later E. L.

Johnson and A. L. Johnson operated the still and the turpentine business. R. H.

Smith operated a cotton gin. Frank McDonald around 1905 described the city as

exceedingly prosperous because of its agricultural business. The well paid

employees of the cotton gin traded in Hawthorne. The boll weevil ended the Sea

Island cotton business after the first years of the twentieth century.

Hawthorne found new sources of income. McDonald mentioned the kaolin deposits

and clay suitable for brick. During this period a union station was built by

the railroads a few feet north of Waits Crossing.

African-Americans as well as white families built homes in the early years of

the twentieth century. The old Gussie Robertson house and the Herring house

were frame homes built by their owners in 1900 on Brown Street (now NW 3rd

Avenue). The New Hope Unit ed Methodist Church was built at 301 SE 2nd Avenue

in 1907. Most African-Americans were employed in farming, turpentine

production, and railroad work. The two Jenkins were builders, along with

skilled craftsmen Ed Brown, the Stitts, and E. J. Williams, carpenter. The

Stitts house on West Lake is a landmark in Hawthorne, because after the second

story burned, it was removed. The house was re-roofed, making it an unusual

appearing one-story house.

The Stock-Sherouse and Mahan houses were constructed on West Lake Avenue, a

fine road that runs from the town lake on the east to Gainesville on the west.

The wide verandah on the Mahan house was a feature of Hawthorne homes, but many

have either been enclosed or taken down. The Barnett-Holden house was built

around 1910 by dry goods merchant Barnett at 101 NW 2nd Street. T. C. Holden

,who had a turpentine business in the 1920s, acquired the house. Later, it

became the Nally house and now is owned by the First United Methodist Church.

Lifelong Hawthorne resident Francis Moore was born in 1917 in the house his

parents bought on West Lake; it was built by Hawthorne builder Charles Birt.

The Frank and Blanche Morrison house was built on West Lake in 1916. On Johnson

Street the Hammond Warehouse and the McMeekin Feed store buildings were

constructed. The first bank in Hawthorne was organized in 1911 on a lot donated

by F. J. Mammond; A. L. Webb was the first president. Later, the building

became a drugstore; the antique mirrored bar inside was moved from

Jacksonville.

The Umberger Additions were recorded on June 23, 1913, along with Lottlefield's

Additions, a subdivision of six blocks. Hawthorne in 1913 had a bank boasting

$15,000 in capital, six daily mails, telephone and telegraph service, four

general stores, three hotels, two furniture shops, a drug store, and a butcher.

One general store advertised an annual income of $200,000 from its sale of dry

goods, groceries, hardware, and furniture items. The proprietor also offered undertaking

services, and had a cotton gin. It was said that at one time this gin produced

more bales of cotton than any Sea Island ginnery around.

Hawthorne also had good clay roads, and a busy social life. Associations like

the Masons, Odd Fellows, and Woodmen of the World met, as did the Eastern Star

and the Hawthorne Woman's Club. The house now owned by the Woman's Club has an

interesting history . Build in 1912 by Lulu Peacock, this house served for a

few years as an office for the town physician, Dr. G. M. Floyd. In 1920 Mr.

Hammond donated the lot to the Woman's Club when the group bought the house.

The lot was slightly enlarged by a 1950 gift from the O'Haras, who lived in the

house next door. The O'Hara home was formerly the Presbyterian Church; when the

Church failed to attract enough members, the congregation disbanded and sold

the structure to Mr. O'Hara, who remodeled it. Mrs. O'Hara still lives there.

Charles Birt, who built several Hawthorne houses, built his own home on NW 1st

Avenue. In this same vicinity, the First United Methodist Church congregation

added the Old Parsonage to their lovely church and grounds. On Johnson Street a

house was built in 1915 that would by live in by Mrs. Arnow, a cousin of the

Morrisons. Later, Mrs. Arnow installed the first Hawthorne telephone exchange

in her front room.

Hawthorne residents continued to lead in the fight against school

consolidation. Robert B. Weeks, Hawthorne merchant and grower, served on the

Alachua County School Board for 16 years, from 1903 until 1919. During the last

two years of his service, Hawthorne succeeded in being designated a Central

School location. In 1920 other small schools in the vicinity were being closed,

and students sent to Hawthorne: Grove Park in 1920, Orange Heights in 1923,

Lochloosa in 1923, Godwin in 1923; Campville in 1923. The loss of the local

school in a small rural community is great; the rural school is an integrating

force offering regular social contacts, a focus for public life, a place for

political rallies, spelling bees, declamations, and required public

examinations. Parents, families, and friends attended. The positive effects for

Hawthorne involved not only keeping the schools, but also increasing the years

of attendance for students. In the 1920s Hawthorne had school through senior

high level; despite an attempt to consolidate the high school in 1953,

Hawthorne today has integrated schools offering the full public school program

from kindergarten through senior high. The town pulls in students from outlying

areas; Hawthorne students score well on competitive tests like the SATs.

Boom Times in

Hawthorne

http://www.sbac.edu/~shell/hawthorne/history.html

prisoners were leased to corporations and

individuals to work in a myriad of industries (such as phosphate mining and

turpentining). The state was paid a fee from the leasee and the leasee had to

clothe, feed, house and provide medical care for the prisoner. At first lessees

paid a mere $26 per annum for each convict with the understanding that they

were responsible for feeding, clothing, housing and providing medical care.

When the state realized these leases were lucrative opportunities, those in

charge raised the cost to $100 per annum, then $150, which still provided

lessees profitable returns.

http://www.dc.state.fl.us/oth/timeline/1877-1895.html