The Geology

of the Barmouth and Arthog area

Bernard

O’Connor 2005

Coming on annual holidays

to Arthog for over a decade I have researched and published two editions on the

history of Mawddach Terrace, fine Victorian town houses on the south bank of

the estuary. Wanting something else to research I found some 20th

century academic papers and books about the geology and geography of North

Wales. I wanted to better understand the Barmouth and Arthog area and spent

time discussing Arthog’s history with Adam Cromarty, who also shed some light

on the local archaeology. My aim was to learn more about the geology and

archaeology on both sides of the Mawddach estuary, but particularly its western

end between Barmouth and the Tal-y-Llyn valley. What follows has been largely

extracted from A. Cox and A. Wells’ 1927 ‘Geology of the Dolgelley district’,

A. Miller’s 1946 ‘Some physical features related to river development in the

Dolgelley district’, G. Howe and P. Thomas’ 1963 Welsh

landforms and scenery, and J. Challinor and D. Bates’ 1973 ‘Geology explained in

North Wales’.

In the back of Cox and

Well’s 1927 account of the geology of the Dolgellau area is their geological

map. It looks very complex. I worked out that in the roughly 8½ miles (13.6

km.) between Barmouth and the Tal-y-Llyn there are eighteen different rock

strata covering a period of about 570 million years. The average thickness of

each seam was just under half a mile (800 m.).

The earliest rocks north

of the Mawddach estuary are Cambrian, originating in what geologists call the

Lower Palaeozoic Period, between, according to the timescale of the British

Geological Survey, 545 and 495 million years ago (mya). This was a much warmer

period when what became Cambria was south of the equator, close to where Namibia

is today! Huge surges in convection currents in the magma deep beneath the

earth’s surface caused massive displacement of Pangaea, the crust. What was

called in the early 20th century ‘continental drift’ and later

‘plate tectonics’ sent the Laurasian continental plate, part of which contained

Wales, northwards at the start of a long winding journey to its present

position in the mid-northerly latitudes.

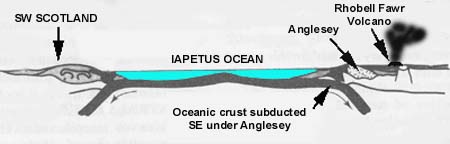

This area of northwest

Wales was a marine basin, termed by geologists the ‘Welsh Basin’ on the south

side of the great ‘Iapetus Ocean’. To the north lay the ancient volcanic rocks

of Canada, Greenland, Antrim and Northwest Scotland and the rest of Northwest

Europe to the south. Although the extent of the Welsh Basin varied with changes

in sea level, it stretched roughly from the English Midlands through Shropshire

to Ireland.

The Iapetus Ocean about

520 mya.

(http://www.cambriangoldfields.co.uk/geology.htm)

As the oceanic crust was

subducted, forced underneath the coninental plate about 510 mya, enormous

pressure built up resulting in the eruption of the Rhobell Fawr volcano, near

Bala. Huge deposits of ash around the Rhobell Fawr area, near Bala. As

it erupted out of the sea, rocks from deep underground were metamorphosed,

heated and pressurized as water percolated through faults and bedding planes.

The heat of the water dissolved metals from the rocks, and, when they cooled

and solidified, these were redeposited as metal ores such as copper and gold.

The Rhobell Fawr volcano

about 510 mya.

(http://www.cambriangoldfields.co.uk/geology.htm)

Heavy tropical rains fed

into continental rivers that discharged mud, sand and grits into the depths of

the ever-widening Iapetus Ocean. Coarser, heavier sediments accumulated at

shallow depths close to shore and the finer material was deposited further out

to sea. It has been estimated that the

deepest, oldest sediments accumulated at depths of about 22,200 feet (6,000 metres).

Over time they were compressed to become hard slates, gritstones, sandstones

and softer shales. Sedimentation rates

have been estimated at one centimetre every thousand years. Over a million

years, ten metres would have accumulated. Compression by the weight of the

overlying sediments has been estimated

to reduce the original strata by two thirds so the ten metres would eventually

be compressed to three, 6,000 metres to 2,000.

These strata continued to

be buried under similar deposits of mud, sand and grits during the Ordovician

period, about 495 - 443 mya. The 19th century geologists who coined

the term, named it after the ‘Ordovices’, the last Welsh tribe to submit to the

Romans. Widespread submarine volcanic

activity during this period resulted in intrusions of volcanic rock into the upper

strata and extrusions of lava through them. When the Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon)

volcanic system erupted from the sea it is estimated that sixty cubic

kilometres of debris was thrown into the air, much more than Mount St Helen’s

explosion. Some settled in the sea to the south to produce deep layers of

volcanic ash.

Yet more shales and

sandstones were formed during the Silurian period, 443 – 417 mya. The ‘Silures’

were a tribe from South Wales. The ancient ‘basement’ beds below the sea were

crumpled during the Caledonian mountain building period about 400 mya. This

resulted in the fold mountains of Southern Scotland. The more recent sediments

that emerged above sea level were exposed to the agents of erosion – waves,

wind, rivers and ice – and removed. Further submergence then followed and more

deposition occurred. These and the earlier strata were further deformed during

the Hercynian mountain building period between 340 and 230 mya. It was during

this period when the continent of Africa collided with the Eurasian plate and

North America continent. These plate movements resulted in the deposits in the

‘Welsh Basin’ being pushed up above sea level to produce a geosyncline – a

mountain range, termed by geologists the ‘Harlech Dome’. Throughout most of

these few hundred million years this area was still beneath the sea and moving

inexorably northwards at an approximate rate of 1 o latitude every

seven million years!

The huge forces released

during the Caledonian Earth Movement, resulted in the NNE to SSW trend of North

and Central Wales. The older Upper Cambrian rocks dip very steeply eastwards.

Exposures of the rocks in the Barmouth and Arthog area show strata averaging

angles of between 40o and 60o but in places up to 90o.

Many glacial advances and

retreats have occurred during the last few hundred million years of the Earth’s

history. The glaciations during parts of the Ordovician and Silurian periods,

between about 460 and 430 mya., affected the land masses surrounding the Welsh

Basin, probably reducing the rate of deposition as the rivers froze. Further

glacial periods during the Carboniferous and Permian periods between about 350

and 250 mya. would have removed much of the newly exposed Harlech Dome. During

the late Neogene to Quaternary period, the last 4 million years, somewhat less

extensive glaciations occurred, but, over the last two million years, there

have been over 20 glacial advances and retreats. If "ice age" is used

to refer to long, generally cool, intervals during which glaciers advance and

retreat, we are still in one today. Our present climate represents a very

short, warm period between glacial advances.

Over the last 320 million

years it has been estimated that over 20,000 feet, (about 5,400 metres) of

strata from the Harlech Dome has been removed by the agents of erosion. As the

land emerged above sea level, the softer upper rocks were dried out by the sun and wind. The contraction and

shrinkage weakened the rocks but the immense pressures during the Caledonian

uplift that created major faults and minor cracks or joints in the rock strata

shattered them. Wind, rain, rivers, freeze-thaw and more significantly ice,

eroded the landscape and redeposited new sediments in the Irish Sea. In more

recent geological times, only about 16,000 years ago, the Cambrian ice sheet

plucked, scraped and carried away the rocks to lower the land surface even

more. Man’s action using dynamite is negligible compared to the natural agents

of erosion.

Using Howe and Thomas’

1963 generalised geological cross section of the area between Snowdon and

Caider Idris, the estimated height above sea level of the strata above Rhinog

Fawr was 26,000 feet (9,620 m.) – about the height of Mount Everest! Above the

Mawddach estuary it was 20, 500 feet (7,585 m.) and above Caider Idris was

16,000 feet (5,920 m.). Marine denudation, the gradual lowering of the surface

by constant tidal erosion, is thought to be the main explanation for the

present landscape. However, being covered by ice sheets during various ice

ages, many billions of tons of the Silurian, Ordovician and Cambrian strata

have been removed. Much of lowland England’s sands, grits and clays consist of

Welsh rock flour, ground up sedimentary and volcanic rocks from not only the

Harlech Dome but other parts of Wales, Scotland and Northern England.

Aerial Photograph looking east of Barmouth and

the Mawddach Estuary

Aerial Photograph looking east of Barmouth and

the Mawddach Estuary

http://www.tlysau.org.uk/en/blowup1/342

The first geological

mapping of this area started in 1846 and one-inch maps were published in 1850

and 1854. Examining Cox and Well’s 1927 geological map of the Dolgellau

district, the rocks north of the Mawddach are many hundreds of millions of

years older than those further south. Barmouth has been built at the foot of

the ‘Hafotty Manganese Shale’ cliffs. These grey and green shales extend for

some 1,000 feet (270 m.) roughly north to south. A bed of between 10 to 20 inches

(30 – 60 cm.) thick manganese ore, which yielded between 20% and 35%, was

worked north of Barmouth in the 1830s but more extensively along its outcrop on

the northern and eastern slopes of Diffwys. They formed as a chemical

precipitate in the Welsh Basin as a close-grained, hard, heavy splintery rock

made up of a mixture of manganese carbonates, silicates and other minerals.

Aerial photograph of

Hafoty Manganese mines north of Barmouth. 1993

http://www.tlysau.org.uk/en/blowup1/7957

Above the Manganese shales lie the ‘Gamlan Shales

and Barmouth Grits’. These make up the high, steep, rough crags of Llawllech

and run roughly north to south east of Barmouth. You can see the exposed grey

rocks on the hill tops, notably Garn, Ffridd y Craig, Craig y Grut and the

2,462 feet (750 m.) high Diffwys. Where they reach the coast they had to be

blasted with dynamite in the 1850s to allow the construction of the railway

line. In the Egryn area, north of Barmouth, the local stone of which almost all of the houses and

boundary walls are built, is a hard,grey sandstone, the Rhinog Grits. According to the National Trust website on

their Egryn property

some of the mullions, door

embrasures and decorative mouldings of Harlech Castle, Cymmer Abbey (near

Dolgellau) and also Egryn Abbey itself are constructed from sandstone of quite

different character. This was quarried at Egryn.

A document relating to the building of Harlech Castle

mentions payment for shipping stone from the 'free quarry at Egrin' (a

freestone quarry). A timber trackway was exposed on the beach at Egryn in

the 1970s and excavated soon after. This has been radiocarbon dated to the same

period of historic building activity, and could well be linked.

Many of Barmouth’s early

houses were built out of the slate blasted from the quarry (SH 617156). You can

also see it exposed in the cuttings along the north side of the A494 as you

leave towards Dolgellau (SH 618156). The metal grill bolted onto the almost

vertical rock face prevents falling rocks and boulders. The angle of the beds

is about 70o from horizontal, which indicates really enormous earth

movements.

Mawddach Falls and Gwyn Gold Mine,

Merionethshire

http://www.tlysau.org.uk/en/blowup1/14590

![Postcard of Mawddach Falls and Gwyn Gold Mine, Merionethshire [image 1 of 2]](Arthog's%20geology_files/image007.jpg) Postcard of

Mawddach Falls and Gwyn Gold Mine, Merionethshire

Postcard of

Mawddach Falls and Gwyn Gold Mine, Merionethshire

http://www.tlysau.org.uk/en/blowup1/14594

Once over these deposits,

you cross the younger ‘Clogau Beds’. They are the same as the ‘Menevian Beds’

in South Wales. The junction lies roughly along the route of the minor road

that goes northeast up the hill along Llwyn Onn. These 250 feet (75 m.) thick,

dark blue to black slates can be seen above Porkington Terrace above the

northern end of Barmouth Bridge (SH 618157). They stretch northeast towards

Carrig y Cled where a major north-south fault and a series of clockwise faults

break it up.

It was claimed in 1927

that the Clogau slates were the oldest formation in the Dolgellau district to

contain fossils. They were first recorded in 1866 and include Paradoxides davidis, P. hicksi,

Centro-pleura henrici Salter,

Eodiscus (Microdiscus) punctatus Salter,

Agnostus punctuotus Angelin, A.

barrendei Salter, A. nudus Beyrich, A barlowi

Belt, A. exeratus var, tennis Illing as well as various brachiopods and

other fossils.

Rich in pyrites the Clogau

slates have weathered to a yellow colour. In places there are intrusions of

volcanic greenstone, which contains gold and copper ore. These occurred many

millions of years after the Clogau beds were deposited, probably when they were

still beneath the sea. Red-hot groundwater forced its way through the overlying

sediments, dissolving the surrounding rocks and metamorphosing (chemically

changing) them.

These volcanic intrusions,

when they cooled and solidified, left bands of gold, silver, iron, copper,

galena (lead) zinc, cobalt and quartz. If you are seriously interested you’ll

need a good dictionary or Internet research to find out what other minerals

have been found. More recent research has identified sulphide

minerals comprising of pyrite, pyrrhotite, chalcopyrite, sphalerite and

arsenopyrite. Rarer species include acanthite, bismuthinite, boulangerite,

bournonite, cubanite, matildite, mackinawite, pyrargyrite and tetrahedrite.

Locally, tellurides of bismuth, lead and silver occur, the most important being

tellurobismuthite and tetradymite, regarded in Clogau as good indicators of

nearby gold. Rarer tellurides include aleksite, altaite, hedleyite, hessite,

nagyagite and pilsenite. The quartz veins range from two to over 100 feet (0.74 m. – 37

m.) thick.

Aerial photograph of the river Mawddach

and Cadair Idris, 1999

http://www.tlysau.org.uk/en/blowup1/389

Although the Romans dug gold in Glyn Cothi, Carmarthenshire, there’s no evidence they had mines in this area. Whether it was worked in the following centuries is uncertain. The Cistercian monks of Cymer Abbey had ‘the right in digging or carrying away metals and treasures’.

It was during the

Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries that

major mining operations started across the region. Recognising the various mineral

and metal ores was a valuable skill. Venturing up river valleys you can still

find rocks that give you clues about the surrounding geology. The chapter in

Hugh Owen’s The Treasures of the Mawddach

provides a valuable history and photographs of local gold mining. Gold was said

to have first discovered in the Mawddach valley in 1834 but not mined until

1847. At one time there were 24 gold mines in the Mawddach valley. The Clogau

(later renamed St David’s) Mines started in the hills above Bontddu where the

beds were cut through by the Afon Cwm Mynach. There were works on both sides of

the valley (SH 664198 and 682202) and lasted about twenty years. It started a

gold rush attracting entrepreneurs from across the country and workmen from the

tin mining areas of Cornwall. Other nearby workings were found further

northeast near Cesailgwym (SH 698212) and on the western banks of Afon Wnin (SH

711214). The Gwynfynydd mine in the Coed-y-Brenin forest exploited the same

Clogau gold. Although it closed down at about the same it was reopened in the

1990s using more sophisticated technology. It is quite a tourist attraction.

There is a record of a 130

ounce lump of quartz and gold yielding 116 ounces of retorted gold. Between

1861 and 1907 over £400,000 was realised from 117,913 ounces of Merionethshire

gold. Tradition has it that Queen Mary, The Duchess of Kent and the Prince of

Wales used pure Merionethshire gold for their wedding rings. It was also used

for the regalia at the Prince of Wales investiture at Caernarfon and the St

David’s Gold Cup for Harlech Golf Club. St David’s mine closed in 1910 and the

buildings dismantled. The seams were not

exhausted as the mines have been worked intermittently since, probably after reports

of gold being found in the estuary between Llanelltyd and Penmaenpool. Even

Australian and Californian prospectors worked in the estuary. In the 1970s Rio

Tinto Zinc were refused planning permission to sift through the alluvial

deposits at the Barmouth end of the estuary and use modern technology to

extract the particles of gold washed out by the 19th century

workings.

The next strata are the

‘Maentwrog Beds’ named after the exposures south west of Ffestiniog. These

2,700 feet (about 1,000 m.) thick dark grey shales run northeast along the

northern banks of the Mawddach estuary, through Bontddu. These beds mark the

start of the Upper Cambrian period, about 520 mya. A section can be seen in the

cutting on the A496 as it drops to the edge of the estuary (SH 622157). They

can also be seen along the new Panorama Walk. In a few low-lying areas alluvial

beds have built up over them, for example below Caerdeon (SH 650177).

Weathering has resulted in them having a rusty red colour. The trilobite Olenus has been found in these beds,

which marks the upper Cambrian age, as well as the little Agnostus.

The Maentwrog shales

stretch further south deep beneath the Mawddach estuary. In Austin Miller’s

work on the river development in the Dolgelley district he estimated that the

deepest part of the sediments is over 120 feet (44 m.).A bore hole drilled

during the reconstruction of a caisson at Barmouth Bridge went through

sediments 76 feet (28m.) thick.

H.W.M.O.S.T +12

ft. O.D.

L.H.W.M.O.S.T. -5 ft

Ground level -20

ft

Dirty Sand and large stones 13

ft -35 ft

Probably the stoning of shifting sands in the foundation of

the original bridge.

Clean coarse sand 2 ft -37

ft

Clear Mud 27

ft -64 ft

Stiff mud and oyster shells 4 ft -68

ft

Blue Clay 8 ft -76

ft

“Granite” rock

(Miller, A.A. (1946), Some

physical features related to the river development in the Dolgelley district, Proc. Geol. Ass. Vol. 57, p.201)

On the south bank of the

estuary the ‘Ffestiniog Beds’ are exposed. These are 3,000 feet (1,110 m.)

thick hard shales and compact fine grits named after the exposures on the

northern slopes of the ‘Harlech Dome’. They date from about 500 mya. Being more

resistant than the adjoining deposits, they have been much less eroded leaving

what at one time were the islands of Ynysgffylog (SH 639138), Fegla Fawr (SH

629147), Fegla Fach (SH 638154) and Coed-y-garth (SH 661168). Exposures on

Fegla Fawr show beds at angles of over 80o with bands of white

quartz.

Further south is Arthog

Bog (SH 635145), thought to be an abandoned ancient river channel which silted

up when the river migrated further north. Deep beneath the peat are first the

softer ‘Dolgelley Beds’. 600 feet (75 m.) thick black shales and mudstones,

rich in iron sulphide.

Where they are exposed

further upstream on both sides of the A493 northeast of Arthog, one can see

traces of worm tracks and worm casts which suggest the beds accumulated beneath

the waves close to the shore. In other exposures fossils of Olenus truncates Brunnich, O. gibbosus Wahl, Agnostus reticulatus Angelin, A.

pisiformus var. and obesus Belt

have been found.

In the lower Dolgelley

beds were found Parabolina spinulosa Wahl.

In the middle beds abundant fossils of Orthis

lenticularis were found and in the upper beds densely crowded but

fragmented remains of Peltura

scarabaeoides Wahl, small trilobites, the most common being Spherophthalmus adatus Boeck, Agnostus trisectus Salter, and various

species of Cytenopyge.

Buried beneath the

southern edge of the bog are the softer ‘Tremadoc Beds’, 1,000 feet (370 m.)

thick coarse grey slates. They date from 491 to 483 mya. The upper beds of the

Tremadoc period, seen immediately below the Arthog War Memorial (SH 629135),

indicate a shallower sea during a period of uplift and folding with the coast

exposed to the elements. There is what geologists call an unconformity – an

absence of beds between the Cambrian and the subsequent Ordovician beds due to

severe erosion. The quarries at Friog (SH 620121), Tddyn Sieffre (SH 632133)

and Ty’n y Coed (SH 652153) exploited the Dolgelley and Tremadoc slates.

Exposures further east

contain fossils of Dictyomena and Lingulella davisii McCoy, evidence that

they were deposited in deeper, quieter waters than the older Maentwrog and

Ffestiniog beds. Found in the upper beds of the Tremadoc shales were

brachiopods, occasional trilobites (Olenus

micrurus), remains of Hymenocaris

vermicauda Salter and markings of Cruziana

simplicata Salter.

The earliest of the

Ordovician series emerge to the south of the Tremadoc slates. The ‘Arenig Beds’

outcrop on the southeast side of the A493 between Arthog and about a quarter of

a mile (400 m.) east of the War Memorial. These dark, rusty ‘flag’ shales

contain grit and ash. In places there are massive beds of ‘Calymene ash’,

evidence of early volcanic activity in the Rhobell Fawr area. This occurred at

the Cambrian-Ordovician boundary about 510 mya and resulted in the creation of

one of the world’s oldest porphyry copper deposits – a huge 200 million tonne

mass of intrusive diorite impregnated throughout with iron sulphides and

copper. They stretch SSW above Fairbourne and NE for about four miles (6.4 km.) before petering out just past the

Afon Gwynant.

Two bands of dolerite

intrusions, basic lava that broke through the earth’s crust, outcrop within the

Arenig beds. More extensive beds are found exposed further east between

Mynydd-y-Gader and Bont Newydd. The

upper strata of redeposited ash, quartz pebbles, felsite and grit indicate

submergence beneath the sea. Cross-bedding indicates strong torrents around

what would have been volcanic islands.

Above the dolerite are

what are called the ‘D bifidus beds’,

up to 600 feet (222 m.) thick, named after abundant fossils found in them.

These contain beds of dark blue, soft Cregennen slates thought to have been

deposited in a swampy grass hollow, and then covered with further volcanic ash

and grits. The lower beds contain a band of rhyolitic tuff, a volcanic deposit

as well as evidence of pyroclastic flows. As a result, these beds have few

fossils but near Cregennen were found primitive planktonites called graptolites

including Didymograptus bifidus, D.

stabilis, D. artus, D. nanus, sp., Climacograptus and occasional

trilobites. Further east towards Caider Idris a 20 feet (7.4 m.) thick exposure

of andesitic lava shows significant volcanic activity. It is quite probable

that the intense pressure build up during the Caledonian Earth Movement led to

it being released dramatically by massive faulting which broke the earth’s

crust and allowed magma to rise to the surface.

Immediately above the D bifidus beds two NE – SW faults, about

twelve miles long, resulted in the ‘Lower Basic Volcanic Group’. In places these rocks are up to 1,500 feet

(555 m.) thick and include rhyolite, pillow spilitic and basalt lavas from the

Caider volcano, overlain by more ashes. (Caider Idris means the chair or seat

of Idris, a mythical Welsh giant.) Below Caider the

lime-rich pillow-lava band in the lower basic rocks of Cader Idris can be traced as clearly by botanists as it can be by geologists, because along that band, but not above or below it, grow calcicole (lime-loving) plants such as green spleenwort, bladder fern, purple saxifrage, lesser meadow-rue, mountain sorrel, hairy rock-cress and numerous calcicole mosses.

(Condry, W. M. (1966) Snowdonia National Park, Bloomsbury

Books, London)

In some places the Cefn

Hir ash is up to 500 feet (185 m.) thick indicating a major volcanic eruption!

They extend from just beyond Cregennan Lakes through Ffordd Ddu (SH 660143) SSW

to include the 1,240 feet (459 m.) high Pen-y-Gern (SH 627108). The Cregennen

granophyre (acid lava) sill, about 1,200 feet (444 m.) thick outcrop of dark

magma extends about five miles (8 km.) through Pont Kings to Llyn Gwernan (SH

704160). Being so hard and resistant to erosion it slopes at about 60o

above Cregennen. The Cregennen Lakes are found on its western edge. It is

covered by alluvial deposits on both sides of Afon Arthog (SH 654136)

A further volcanic feature

outcrops further up the slopes of Cader. It is about 2,000 feet (740 m.) thick

and extends for about three miles (4.8 km.). It is a laccolite, an upthrust of

magma which cooled down before it reached the surface because of overlying

older lavas. It was subsequently exposed by erosion. The Cregennan sill and the

Caider laccolite were thought to have occurred during the Upper Acid Volcanic

event.

The rocks of the Lower

Basic Volcanic Group are covered by Llyn-y-Cader shales, at the base of which

is a band of oolitic iron ore. This chemical sediment in the Welsh Basin is

thought to be the action of bacteria and algae. It is similar to the Jurassic

oolitic rocks of the East Midlands but more deformed and metamorphosed and

contained magnetite. The band was too thin to be worked profitably at Caider

but at Cross Foxes (SH 760164) a 20 feet (7.4 m.) thick seam was exploited.

Graptolites were found in these shales including Nemagraptus gracilis and Glptograptus teretiusculus His.

To the south of Ffordd Ddu are extensive beds

of ‘Llyn Cau mudstones’, about 500 feet (185 m.) thick. Afon Dyffryn drains

southwest across them from Braich Ddu to join Afon Gwri. The alluvial deposits

around Afon Arthog mentioned earlier also cover part of these mudstones,

originating immediately below Llyn Cyn (SH 657118). They extend further east to

include the southern slopes of Tyrau Mawr (SH 680132).The upper beds contain

ash and broken feldspar, evidence of yet more volcanic activity.

A thin band of the

‘Llyn-y-Cader mudstones’ outcrops immediately below the summit of the 1786 feet

(661 m.) high Craig Las (SH 677136). Just below Craig-y-Llyn you can see the

‘Upper Acid Volcanic Group’. They are made up of Andesitic tuff and Andestic

and rhyolitic lavas between 900 and 1,500 feet (333 m. – 555 m.) thick which

indicate massive volcanic activity. The upper beds are covered with a thin band

of breccia lavas and crystal tuffs thought to be the last outpourings of the

eruption. They extend ENE parallel to the Tal-y-llyn-Bala fault.

These volcanic rocks have

been overlain in the upper reaches of the tributaries of the Afon Ddsynni by

grey-blue slaty ‘Tal-y-llyn Mudstones’. In places they are 8,000 feet (2,960

m.) thick. Even younger rocks outcrop further southeast towards Aberllefenni.

This description and

explanation of the geology of the Barmouth and Arthog area has largely been

extracted from the following sources:

Challinor, J. and Bates,

D.E.B. (1973), Geology Explained in North

Wales, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, pp.68-79, 86-100

Cox, A. H. and Wells, A.

K. (1927), The geology of the Dolgelley district, Merionethshire, Proceedings of the Geological Association, Vol.

38 (3), pp. 265-318

Howe, G. M. & Thomas, P. (1963) Welsh landforms and scenery,

Macmillan, London

Miller, A.A. (1946), Some

physical features related to the river development in the Dolgelley district, Proc. Geol. Ass. Vol. 57, pp.174-203)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/northwest/outdoors/placestogo/reserves/coedybrenin.shtml

http://www.cambriangoldfields.co.uk/geology.htm